Podcast with Dr. Hong Li from SBA (Chinese)

As a researcher at the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics IBP in Germany, what is the correlation between your research focus and urban regeneration? Do you have any direct perception on China’s policy changes and evolving trends in urban regeneration? What do you think about the significance of Modeling and AI Simulation in urban regeneration projects? How will the global COVID-19COVID-19 Corona Virus Disease 2019 crisis be reflected in future urban regeneration? As part of our Sino-German City Lab Dr.Hong Li from SBA shares his views on these and more questions. The podcast is in Chinese, see an English summary below:

Dr. Hong Li Podcast Summary (EN)

Could you briefly describe your professional experience and the projects of SBA Architecture and Urban Planning?

Working at the Fraunhofer Institute (fourth from left: Dr. Li Hong)SBA

I studied architecture at Tongji University in Shanghai as an undergraduate, then worked at the East China Architectural Design Institute in Shanghai for a few years before going to Germany to study at the University of Stuttgart. Then I stayed in Germany to work in an architectural firm. Later I came back with a team to start business in Shanghai, and it’s been almost 20 years now. We have been involved in a number of projects for urban regeneration, old city renovation and historical landscape conservation. We also worked on several research projects in Germany. Some years ago, we took part in the German government-backed Morgen Stadt project to study future urban development, in collaboration with the Fraunhofer Institute. Later, I joined the Institute for Building Physics as a researcher. So I am now in a dual role. In the practice area, I am both a partner at SBA and a researcher at the Fraunhofer Institute, doing some research work on digital and smart cities. The year before last we led a collaboration between the Fraunhofer Institute and Shanghai Jiao Tong University to set up a research centre for urban ecological construction at the university.

What was your first project after you returned to China?

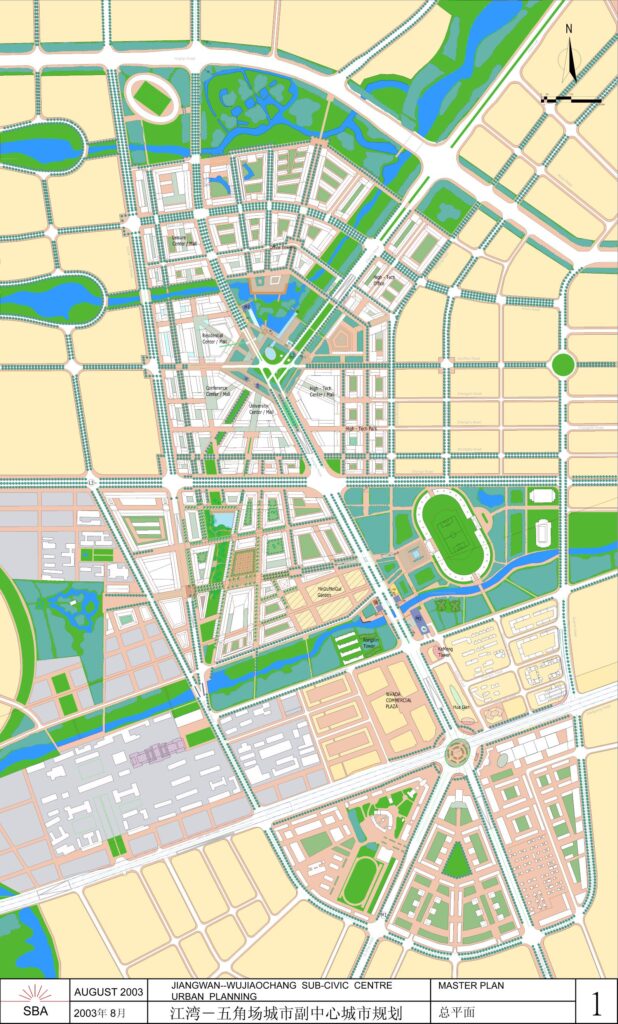

New Jiangwan CitySBA

The New Jiangwan City. I guess it was just starting then, and Shanghai ran an international competition by inviting some renowned firms from overseas to participate. This would be the first relatively large urban regeneration project we joined in China. This is a very interesting project. On the one hand, it was home to a military airport. On the other hand, the Wujiaochang area was designated the first modern urban plan by the Chinese in the 1930s, under the ‘Greater Shanghai Plan’. It has a fascinating checkerboard road network and is also part of the Shanghai Landscape Conservation Area, with some old buildings. You can see a clear combination of East and West architectural styles in the so-called Republican style, with large roofs and many traditional Chinese architectural expressions. However, the pattern and form of buildings are westernised, which was also unique of that time. When we did our planning, we needed to protect the road network, preserve certain buildings and plan for future urban design.

You mentioned that you are a researcher at the Fraunhofer IBP. How is your research direction related to urban renewal?

The Fraunhofer Institute has 74 institutes and over 26,000 scientific researchers, which makes it quite similar to the Chinese Academy of Sciences in terms of scale or nature. It is a research institute for applied science and technology and focuses exclusively on application research, which is directly related to the application of industrial technology in urban development.

When it comes to urban renewal, it involves the development and application of new technologies in transport, energy use, quality of life, and improving the relationship between the city and nature. Urban renewal should first and foremost be a process of optimisation. If we talk about urban regeneration in a narrower sense, we can narrow it down to the renovation of historic areas, especially concerning quality historic buildings, which need to be both protected and reused. The restoration of historic buildings, for example, involves the application of specific materials.

In the process of urban regeneration, whether architectural design or urban design, it must be very well integrated with technology. Digital smart cities are now also being proposed and the Fraunhofer Institute brought forward the notion of Industry 4.0. The building sector will also develop in the direction of intelligence, from BIMBIM Building Information Modeling (Building Information Modelling) to CIM (City Information Modelling), which are all interesting topics in the field of urban regeneration.

Mr. Cao Yongkang’s team at the Jiao Tong University Research Institute happens to be working on digitalising historic buildings for Zhang Yuan. The Fraunhofer Institute has outstanding artificial intelligence modelling technology to support the process. He is still manually archiving and modelling these historic buildings. If there is technology to complete this task more efficiently, it is certainly promising. Once you have taken a few building photos on site, the AI software recognises the photos and automatically creates building models, with some manual corrections, making the process much more efficient.

What is your direct experience of the evolution of urban renewal policies and trends in China?

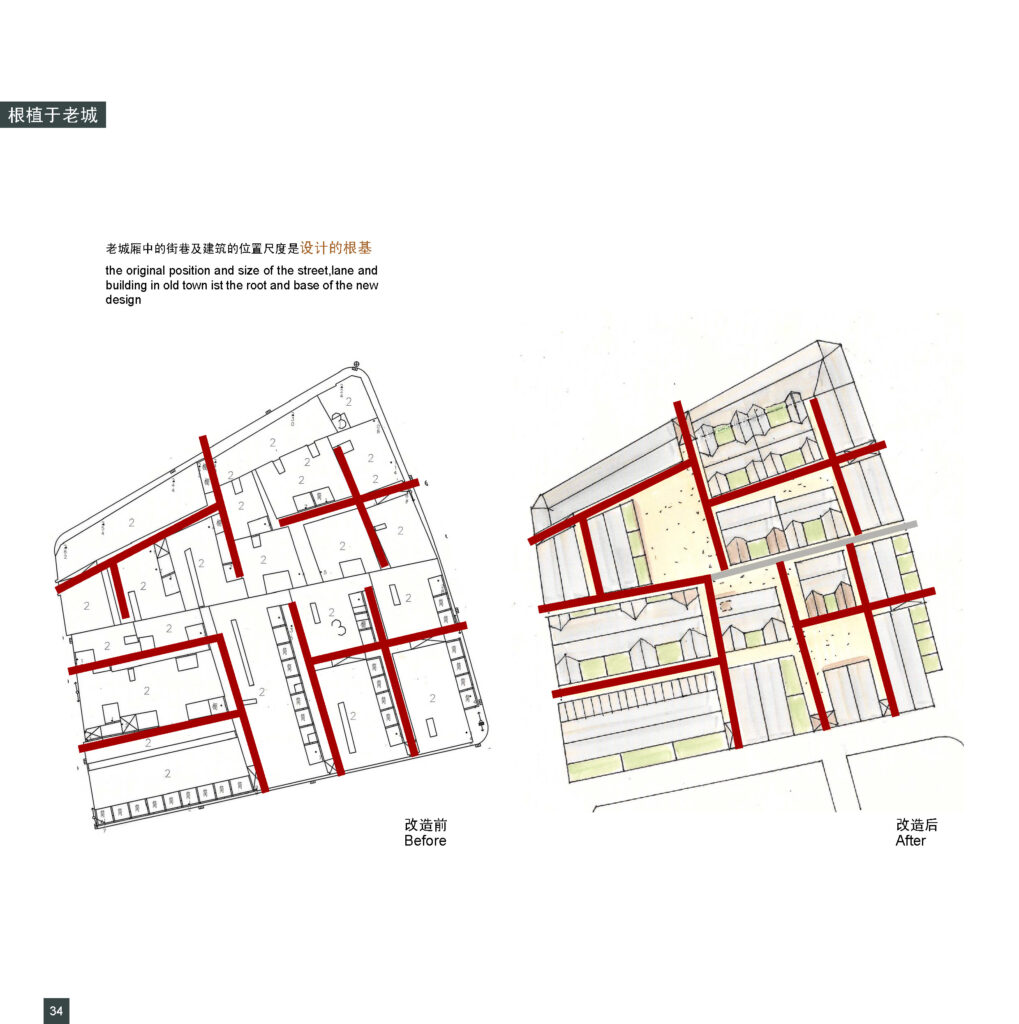

Lu Xiang Yuan Street and building locations and scale before and after retrofitSBA

As an architect and urban designer, I would make a clear distinction between regeneration of historic areas and that of general urban areas.

When renewing historic districts, it is important to maintain existing industrial development, living standards and lifestyles, while at the same time preserving significant and valuable historical features. Since our team arrived in Shanghai, we have been involved in several very interesting historic landscape conservation and development projects. For example, Lu Xiang Yuan, the ancient area around Shanghai’s City God Temple, was like a walled city. There used to be city walls around it and a checkerboard grid of roads. If you go to the area, you will find that apart from this network of roads, there are almost no real historic buildings left. How to carry out such a project in an area where the historic landscape of Shanghai is preserved?

The spatial hierarchy and changes in spatial formbefore and after retrofitSBA

Shanghai Tower and its surroundingsSBA

The two senior partners of our office developed a method to analyse and summarise elements of urban space in a systematic way, both in terms of landscape and architecture. We need to preserve the historic landscape, but what? The German designers provide a good reference. For example, the spatial scale, the alignment of road network, the height to width ratio of the street, the building roof slope, and the façade alignment are extracted and analysed. These elements play a key role in the urban landscape. We have then mastered a method to preserve the urban landscape well, or to restore it, even in cases where the buildings are not necessarily worth preserving and need to be renovated.

Shanghai Tower and its surroundings

Applying this approach to the Shanghai Tower and the surrounding area, there is no doubt about the preservation of famous historic buildings such as the Astor House Hotel, the Shanghai Tower, the Russian Consulate and the Waibaidu Bridge. Preserving the buildings whilst adapting them to new uses, the focus of retrofit or renewal should be on the exterior spaces. I think urban designs that serve the current lifestyle, fit the historic landscape and match these historic buildings are valuable. We need to focus on the exterior spaces and the river front landscape, among others.

What should be the focus of urban renewal and urban landscape protection? When a historic area is relatively large in scope, it is impossible to complete the task in a short time. There are many areas that need to be taken care of gradually and by different actors rather than a single one. Different actors are involved in the future development of the city and have their own intentions and tastes.

When designing the Wujiaochang area and the area around the Shanghai Tower, we also adopted a good German working method. This method is now widely used in the field of urban design in China, in the form of guidelines and diagrams. By transforming the designer’s proposal into a set of rules, no matter which architect you hire to realise a specific project in the future, the effective methods have been put in place to ensure concrete urban landscape conservation. The process can be specified with clear details for continuity of urban landscaping.

The concept of organic renewal is also being proposed in China, which regards urban areas as organically growing living organisms. It adopts an adaptive and progressive approach to urban retrofitting.

Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition CenterSBA

It is just as well that we continue the previous topic and talk about urban renewal in general. Urban renewal should be an evolutionary process, like an ecological community. It should be nuanced and gradually evolve, instead of a revolutionary development every time.

It is interesting to see how architects and urban planners participate in this evolutionary process and how they do it. It is a long and detailed process. We can go back to the topic of digitalisation. If we want to make this process better, it is up to the professionals to study or make a value judgement as to how the evolutionary progress should be guided towards sound development. This is the more scientific approach to urban planning and urban design. But in order to do this, you need to have a comprehensive and detailed knowledge of the city. How to achieve this? Nowadays, digitalisation and artificial intelligence have given us the possibility to do so.

Big data in Chinese cities is developing very fast, and IoT (Internet of Things) has gradually developed into IoE (Internet of Everything). Once we have information and data models, it will be easier for us to make simulation and analysis.

Immersive mixed reality space for city-wide digital modelsSBA

The German technology in this area has been developed from the industrial sector, which is called pre-diagnosis. In fact, this concept is very valuable in the urban field. Firstly, we need to find a way to build a digital model. The second is to collect more accurate and valuable information. How do we combine all the different kinds of information and make it work for us? And how to combine these very large databases with our digital models? There are also economically viable technical means to make the models work. We need to find solutions to these problems. With the ideal digital tools, urban regeneration will become a completely different professional process.

We’ve just talked much about digital tools. I would like to go back to the people. How can we support various stakeholders in the project on a human level. What are some of the approaches in Germany that are worth learning from?

If you make an urban renewal project in Germany, the main effort, one could even say 70 to 80 per cent, is spent on communicating with the community representatives and project stakeholders. You need to sort out the interests and different ideas to ensure the success of your urban renewal project.

In Germany, there is even a special profession. My observation is that this all started in recent years. Previously, this was the responsibility of the owner, developer or the urban design or architectural office. Now a new profession has appeared. There are consulting firms that specialise in this area of business, and architects can concentrate on the design and technical work. There are many communication events with the community, sorting out different points of view. I think it’s interesting that these tasks have given rise to a new profession.

How does Germany assess the value of existing buildings in regeneration areas? For example, how do they decide what to preserve and what to demolish?

LH: The costs of renewal is higher than that of new construction, and this is the case all over the world. The costs or value of a building retrofitting project has several dimensions. First is the value of property. The second is the added value, such as cultural value and historical features. The third is the financial costs during construction. When construction is efficient, the cost of finance goes down. The longer the construction period, the higher the costs.

Another aspect is the environmental costs, energy consumption and recycling of materials for retrofitting each building or urban area. It’s different again if you take this into account. To a large extent, the legal system and cultural perceptions determine which parts are ignored and which are given more importance when calculating costs.

I think that when it was more economical to demolish than to retrofit, whether in China or in Germany, a certain component of the costs was actually overlooked. Now that we are more environmentally conscious, if we count climate change and carbon peaking as costs, we might have a new perspective.

How will the global COVIDCOVID-19 Corona Virus Disease 2019 pandemic crisis be reflected in the future of urban regeneration?

We have a team at the Institute working on a research project for the Baden-Württemberg State Government on this very topic. On the one hand, it’s about using the so-called non-chemical means to decontaminate public buildings and spaces for safety. At the same time, the analytical capabilities of digital models and airflow temperature models are used to anticipate potentially risky areas in public spaces. All of these technological tools concern the question of how to prevent and control the pandemic at lower costs.

Between your different roles in China and Germany and your background, how could you better utilise the strengths of each side to promote Sino-German cooperation in the field of urban renewal?

LH: Our generation lives in a rapidly globalising world, which is something that I feel strongly about at my age. For an architect or researcher such as myself, there is a good and crucial role to play in facilitating smooth cultural exchange and cooperation and especially making the process more constructive, whilst reducing unnecessary conflicts and misunderstandings. I think that is one of the things I can do very well.

Of course, we need to enhance communication of information. For example, let’s go back to the digital city concept. The so-called smart world is a networked world where everything is interconnected. What is the most crucial thing in it? The nodes and degree of connectivity are the most crucial. If there are no active nodes or high connectivity in the network, it will gradually die and cease to exist, becoming scattered again. But if there are active nodes and high connectivity, the network will grow to be solid and active.

If we look at the world or society as a network, I would like to be a more active node with a high degree of connectivity in different cultural areas, and play a good role in facilitating communication. I think I have an active role as a node, which is probably an interesting analogy.

About Dr. Hong Li

Dr. Hong Li, Managing Director SBASBA

Architect and urban planner Dr. Hong Li has been managing director of the office SBA Architektur und Städtebau with offices in Munich, Stuttgart and Shanghai since 2001. As office and project manager in Shanghai, he has realized numerous challenging architecture and urban planning projects in Germany and China since then. His specialty is the development of smart and sustainable cities. In the context of his employment at Fraunhofer, he is also active within various research projects.

Contact SBA China

Shanghai

17th floor | KIC Plaza II

No. 38 | Zhenggao Road

200433 Shanghai | P.R. China

Fon: +86 21 65877922

Fax: +86 21 65877911

E-Mail: info(at)sba-int.com

The Sino-German City Lab is funded by the “Export Initiative Environmental Technologies” (EXI) of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUBMU Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit).